Who are the people you think are fighting for justice today? Painter William H. Johnson thought deeply about this question while crafting his remarkable Fighters for Freedom series in the mid-1940s as a tribute to African American activists, scientists, teachers, and performers as well as international leaders working to bring peace to the world. Through the series, Johnson traces the arc of African American contributions within American history from the Revolutionary War to present and was particularly attuned to Fighters who were making history in his day. Notably, Johnson brings the stories of many Black women to the forefront. We know the stories of some of his Fighters—Harriet Tubman and Marian Anderson are legends—but today fewer of us remember the pioneering educator Nannie Helen Burroughs, or Jane Edna Hunter, who provided affordable, safe housing for Black women working in Cleveland, Ohio.

Johnson elevates the lives of his subjects, offering historical insights and fresh perspectives. Each portrait is punctuated with tiny buildings, flags, and vignettes that give insight into their stories and clues viewers to significant episodes in their lives. He celebrates their accomplishments even as he acknowledges the realities of racism, oppression and sometimes violence they faced and overcame.

Honoring Educators

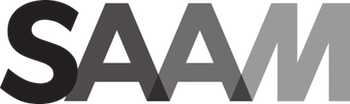

Throughout his series, Johnson highlights many historic and contemporary educators as changemakers. He depicted Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955), one of the most important educators and Civil Rights activists of the twentieth century, twice in the series. She opened a school for African American girls in Daytona Beach, Florida, that merged with the Cookman Institute to form the coeducational Bethune-Cookman College in 1931. Johnson shows students studying anatomy, biology, and dance on the right; his portrait of Bethune anchors the left. In the lower left, she passes the presidency of the college to her successor, James Colston. The two men embracing at the center remain unidentified. They may have been involved with Bethune-Cookman College or part of a coalition of Black leaders Bethune worked with who also served as an informal advisory board to President Franklin Roosevelt's administration (the so-called Black Cabinet). The latter group fought for the inclusion of African Americans in New Deal programs during the Great Depression and was a precursor to the 1960s civil rights movement.

Building Institutions of Change

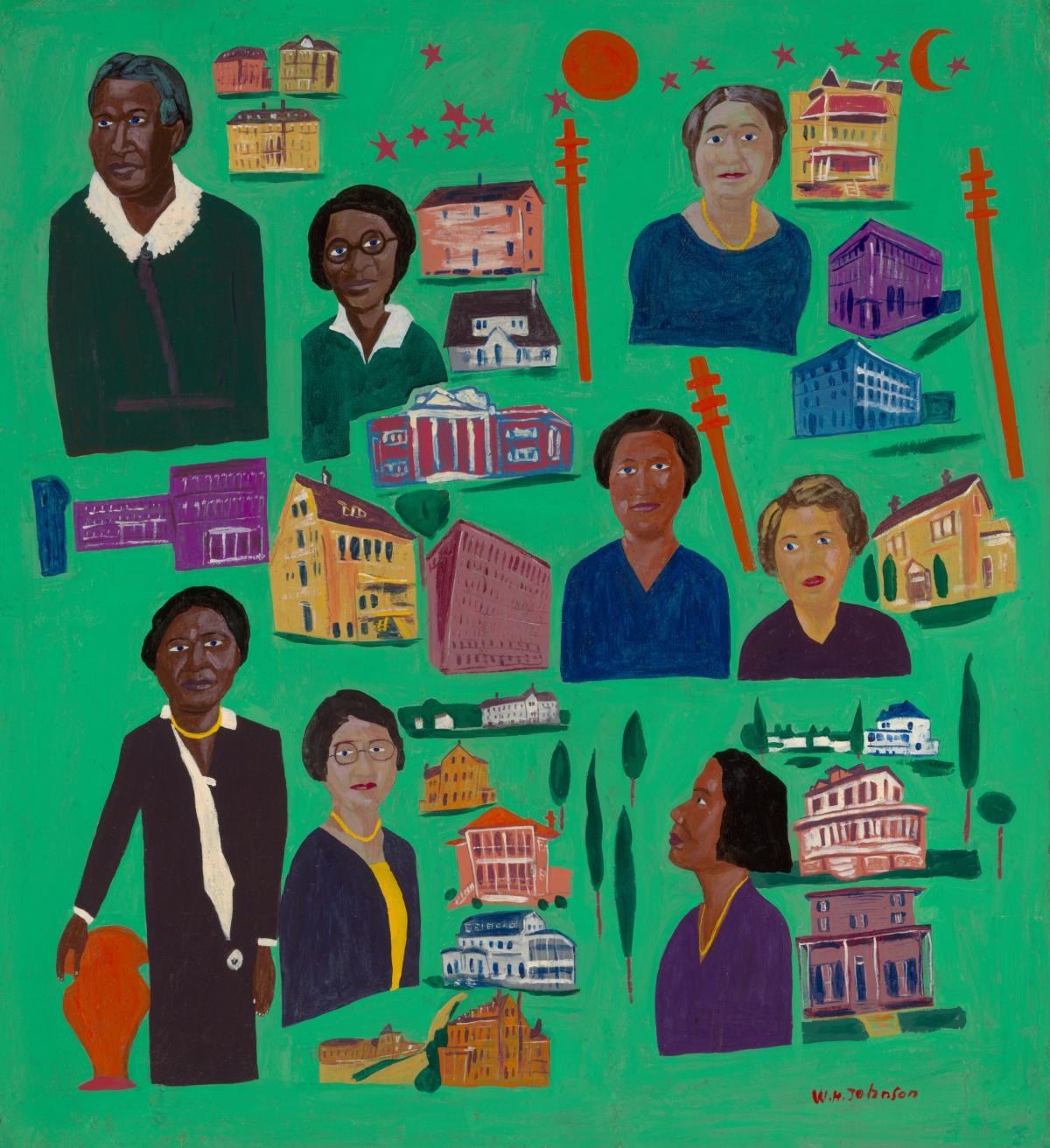

Women Builders depicts a constellation of inspiring and enterprising African American women. Johnson sourced the portraits for the artwork from Sadie Iola Daniel’s 1931 book of the same name. The painting’s eight figures include the author Daniel (middle row, right) and others who provided services and opportunities in African American communities. After the abolition of slavery, many areas of the United States legalized segregation of the races (enacting what are called Jim Crow policies or laws), which left many African American communities without schools, banks, housing, and other resources. These important women filled the void. To underscore the book’s “builders” theme, Johnson paired the women’s portraits with buildings from their organizations. The exhibition catalogue explores the painting’s individual portraits in depth.

Pictured in profile, Nannie Helen Burroughs (1879–1961, bottom right) was an educator, civil rights activist, and orator. Born in Orange, Virginia, Burroughs spent most of her life in Washington, D.C. After she was denied a job as a public school teacher, purportedly because her skin was too dark, she vowed to create her own school. Her fundraising campaign sought support from Black citizens, religious groups, and businesses; banker Maggie Lena Walker (pictured above Burroughs) gave five hundred dollars to the cause. After the National Baptist Convention bought land for the school in northeast Washington, D.C., Burroughs founded the National Training School for Women and Girls. The curriculum offered vocational and academic courses, and Burroughs was the school’s president for the rest of her life.

Burroughs’ skyward gaze suggests her religious convictions and moral vision for racial equality. She assumed leadership roles in the National Baptist Convention, its Woman’s Auxiliary, and the National Association of Colored Women, which fought for women’s suffrage. Some consider her activism a forerunner to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and ’70s. A gifted intellectual, Burroughs was also a writer and orator. Her description of the Allied effort in World War II (from a circa 1943 radio address) could also summarize her own life’s work: “to make the world large enough for democracy and too small for race prejudice, discrimination, injustice and hate.”

Lucy Craft Laney (top row, left) created the first school for Black children in Augusta, Georgia. Another educator, Charlotte Hawkins Brown (top row, middle), founded the Palmer Memorial Institute, a boarding school in Sedalia, North Carolina. In 1903, Maggie Lena Walker, (top row, right) became the first African American woman to charter a bank, the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in Richmond, Virginia. Trained as a nurse, Jane Edna Hunter (middle left), eventually formed a shelter for Black women in Cleveland, Ohio, to ensure their safety and help find jobs for those who had moved from the South. Now well-known, Mary McLeod Bethune (bottom left) founded a school and college in Florida that is today called Bethune-Cookman University. Social worker Janie Porter Barrett (bottom middle) built a settlement house in Hampton, Virginia, and a reform school for African American girls in Hanover, Virginia.

SAAM’s landmark exhibition, Fighters for Freedom: William H. Johnson Picturing Justice, explores Johnson’s series of paintings honoring the achievements of individuals working to bring peace to the world. This story is part of a series that takes a closer look at artworks with material drawn from exhibition texts, the catalogue, and interpretive materials.